On March 27, the New York Court of Appeals unanimously ruled that under a “pro rata time on the risk allocation,” insurers are not liable for years outside their policy periods when there was no insurance available to the insured in the marketplace. See KeySpan Gas East Corp. v. Munich Re. Am., Inc., 2018 N.Y. Slip Op. 02116 (N.Y. Mar. 27, 2018). The decision is a significant victory for insurers faced with long-tail environmental claims, and may also lend support to insurers when allocating losses involving other types of long-term or continuous injury or damage.

On March 27, the New York Court of Appeals unanimously ruled that under a “pro rata time on the risk allocation,” insurers are not liable for years outside their policy periods when there was no insurance available to the insured in the marketplace. See KeySpan Gas East Corp. v. Munich Re. Am., Inc., 2018 N.Y. Slip Op. 02116 (N.Y. Mar. 27, 2018). The decision is a significant victory for insurers faced with long-tail environmental claims, and may also lend support to insurers when allocating losses involving other types of long-term or continuous injury or damage.

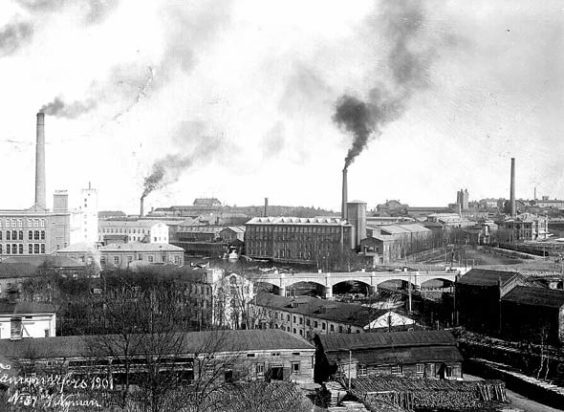

The dispute arises out of KeySpan’s liability for environmental property damage at manufactured gas plants owned by KeySpan’s predecessor and operated in the 1880s and 1900s. Decades after they closed, it was determined that the plants had caused gradual contamination to the soil and groundwater near the sites. KeySpan was required to undertake costly efforts to remediate the sites, and it sought coverage for the costs from its various liability insurers. One of those insurers was Century Indemnity Company (“Century”), which had issued eight excess liability policies to KeySpan from 1953 to 1969.

KeySpan ultimately filed this action against Century and other insurers seeking a declaration of coverage for the cleanup costs under the policies. Only coverage under the Century policies was at issue before the Court of Appeals. As to those policies, several points were undisputed: first, the contamination at issue occurred gradually and continuously before, during, and after all of the Century policy periods, thereby potentially triggering each policy; second, the policies required a pro rata time on the risk method of allocation; and third, for purposes of allocation, KeySpan was to bear the risk for damages that took place during years in which property damage insurance was available to, but not purchased by, its predecessor. The disputed issue was whether, under a pro rata time on the risk allocation, Century was liable to KeySpan for years before and after its policy periods, when pollution damage liability insurance was unavailable in the marketplace.

Against this backdrop, Century moved for summary judgment declaring that it was not liable to KeySpan for periods in which it was self-insured voluntarily or because applicable insurance was unavailable. The trial court granted the motion in part, finding KeySpan was liable for the years in which it elected to self-insure, but it denied the motion with respect to years in which pollution insurance was otherwise unavailable. The effect of the ruling was that Century would be liable for any damage that occurred before 1953 and after 1986. Century appealed, however, and the Appellate Division reversed as to the periods of unavailability. The Appellate Division then certified the question to the Court of Appeals of whether periods of so-called “unavailability” are properly allocable to the policyholder, rather than its insurers.

As a matter of first impression, the Court of Appeals agreed that imposing liability on an insurer for damages resulting from occurrences outside its policy period “would contravene the very premise underlying pro rata allocation.” The court began its analysis with the premise that New York courts look first and foremost to the policy to determine the method of allocation. Citing Matter of Viking Pump, Inc., 27 N.Y.3d 244 (2016) and Consolidated Edison Co. of N.Y. v. Allstate Ins. Co., 98 N.Y.2d 208 (2002), the court noted that policy language restricting the insurer’s liability to occurrences taking place “during the policy period,” as under the Century policies, is more consistent with a pro rata allocation. But where, as here, there are gaps in coverage, the issue becomes whether the insurer or the insured must bear the risk for periods in which no such coverage was offered on the market.

While noting that several jurisdictions outside of New York have addressed this issue by recognizing an “unavailability exception” to the general rule that policyholders are on the risk for periods in which coverage was not obtained, the court refused to endorse such an exception here. The court instead agreed with Century that to do so would be “inconsistent with the contract language that provides the foundation for the pro rata approach – namely, the ‘during the policy period’ limitation – and that to allocate risk to insurers for years outside the policy period would be to ignore the very premise underlying pro rata allocation.”

In so holding, the court rejected KeySpan’s argument that it would be inequitable to allocate years of unavailability to policyholders, noting that the “policyholder is the one who allegedly caused the injury, and therefore, who ultimately will be financially responsible should insurance prove insufficient.” The court’s reasoning indicates that a contrary conclusion is more likely to lead to inequities from the insurers’ perspective. For instance, application of the exception would essentially require insurers to indemnify policyholders for years in which no premiums were paid, and could also “impose liability in perpetuity (or retroactively to periods prior to coverage) on an insurer who issued insurance coverage for only a limited number of years, thereby eviscerating much of the distinction between pro rata and all sums allocation.” For these reasons, the court affirmed the Appellate Division’s order its entirety.

Interestingly, KeySpan is directly contrary to a recent Connecticut Appellate Court decision, R.T. Vanderbilt Company, Inc. v. Hartford Accident and Indemnity Co., et al., 156 A.3d 539 (Conn. App. Ct. 2017) (as discussed here). R.T. Vanderbilt was cited unfavorably in KeySpan and is on appeal to the Connecticut Supreme Court. It is also worth highlighting that while KeySpan resolves a longstanding question frequently seen in the context of environmental claims, it may also lend support to insurers for purposes of allocating liability in other continuous injury cases, such as those involving asbestos and/or other toxic torts. In either event, however, the decision will not impact policies containing non-cumulation or prior insurance clauses in light of the court’s recent decision in Viking Pump.