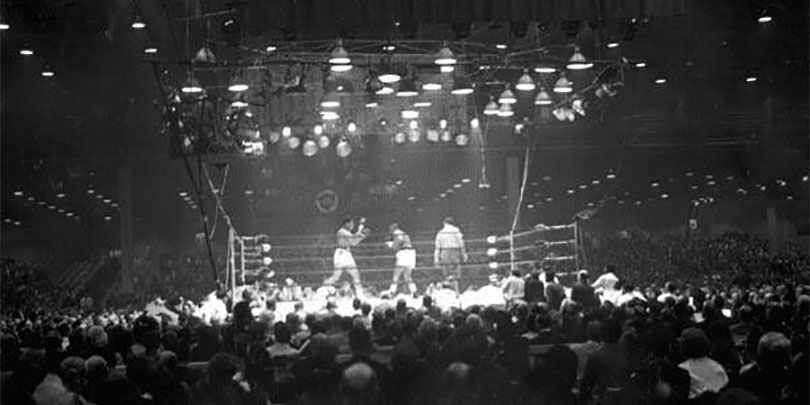

In a bout before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, two heavyweight federal statutes squared off, with coverage for hundreds of long-tail, asbestos-related personal injury lawsuits on the line. In one corner: the Federal Arbitration Act, enacted by Congress to overcome federal courts’ erstwhile reluctance to enforce arbitration agreements. In the other corner: the McCarran-Ferguson Act, created to curb those courts’ over-reach into insurance regulation under the Commerce Clause. The FAA was the victor in Hennessy Industries, Inc. v. National Union Fire Ins. Co. of Pittsburgh, PA, but the “no mas!” moment for this rivalry is still a long way off.

The FAA’s “liberal policy favoring arbitration”

The U.S. Supreme Court has explained the history and purpose of the FAA:

The FAA was enacted in 1925 in response to widespread judicial hostility to arbitration agreements. . . . [and] provides, in relevant part, as follows: ‘A written provision in any … contract … involving commerce to settle by arbitration a controversy thereafter arising out of such contract … shall be valid, irrevocable, and enforceable, save upon such grounds as exist at law or in equity for the revocation of any contract. We have described this provision as reflecting. . . a ‘liberal federal policy favoring arbitration.’

AT&T Mobility LLC v. Concepcion, 131 S.Ct. 1740, 1745 (2011). Thus, “[w]hen state law prohibits outright the arbitration of a particular type of claim. . . [t]he conflicting rule is displaced by the FAA.” Id.

Save me, McCarran-Ferguson!

The McCarran-Ferguson Act was Congress’s response to a 1944 U.S. Supreme Court decision, United States v. South-Eastern Underwriters Assn., 322 U.S. 533 (1944), in which the court held for the first time (i) that insurers doing business across state lines were involved in interstate commerce, and (ii) that they consequently came within the purview of Congress’ regulatory authority under the Commerce Clause. The Supreme Court has explained this one, too:

Concerned that our decision might undermine state efforts to regulate insurance, Congress in 1945 enacted the McCarran-Ferguson Act. Section 1 of the Act provides that “continued regulation and taxation by the several States of the business of insurance is in the public interest,” and that “silence on the part of the Congress shall not be construed to impose any barrier to the regulation or taxation of such business by the several States.” … Section 2(b) provides that when Congress enacts a law specifically relating to the business of insurance, that law controls. The subsection further provides that federal legislation general in character shall not be “construed to invalidate, impair, or supersede any law enacted by any State for the purpose of regulating the business of insurance.”

Humana Inc. v. Forsyth, 525 U.S. 299, 306-307 (1999).

In short, the Supreme Court has held that McCarran-Ferguson “saves” certain state laws from federal preemption—if those laws regulate insurance. To apply that rule, the court enunciated the following test:

First, whether the practice [affected by the law] has the effect of transferring or spreading a policyholder’s risk; second, whether the practice is an integral part of the policy relationship between the insurer and the insured; and third, whether the practice is limited to entities within the insurance industry.

Pilot Life Ins. Co. v. Dedeaux, 481 U.S. 41, 48-49 (1987) (finding that Mississippi’s common law rules concerning “bad faith” did not regulate insurance, and so were preempted by ERISA).

Let’s Get Ready to Rumble

Hennessy Industries is a manufacturer of automobile parts, and it has been faced with hundreds of personal injury law suits filed against its predecessor, dating back to the 1980s. The suits allege that the predecessor caused the plaintiffs to be exposed to harmful, asbestos-containing materials, resulting in asbestos-related disease.

Hennessy’s predecessor was insured at relevant times by policies issued by National Union Fire Insurance Company of Pittsburgh, P.A. and Zurich Insurance Company. In 2008, Hennessy, National Union and Zurich resolved disputed issues of coverage by entering into a cost-sharing agreement (“CSA”), which set out a framework to govern claims handling and payment going forward.

The CSA, which was governed by Illinois law, contained a term that governed disputes over “the application, interpretation, or performance of this Agreement or any rights, responsibilities, duties, or obligations of the Parties” thereunder. It provided: “If any such dispute cannot be resolved by good faith negotiation … the Parties shall submit the matter to binding arbitration to a panel of three arbitrators.” It also stated:

The arbitrators shall not be empowered or have jurisdiction to award punitive damages, fines, or penalties.

Round 1

Ultimately, a dispute developed between Hennessy and National Union regarding the calculation of amounts owed to Hennessy under the CSA, and that dispute was duly submitted to arbitration. Hennessy also alleged, however, that National Union’s refusal to pay the amount that was the subject of the arbitration had been “vexatious and unreasonable.” And a provision of the Illinois Insurance Law, 215 ILCS 5/155(1) (“Section 155”), authorizes a court to award both statutory damages and attorneys’ fees for conduct of that type:

In any action by or against a company wherein there is in issue the liability of the company on a policy or policies of insurance or the amount of loss payable thereunder, … and it appears to the court that such action … is vexatious and unreasonable, the court may allow as part of the taxable costs in the action reasonable attorney fees, other costs, plus an amount not to exceed [either $60,000 or certain other amounts].

To take advantage of that statute, Hennessy filed an action against National Union in federal court, seeking penalties, attorneys’ fees and costs under Section 155. National Union moved to compel arbitration of that claim, but the district court denied the motion, finding that the Section 155 claim was not within the scope of the parties’ arbitration agreement. National Union appealed.

Judge Posner Steps In to Break it Up

On appeal, the Seventh Circuit Court was confronted with two key issues: (1) National Union’s argument that Section 155 does not “regulate the business of insurance.” and so may be preempted by the FAA; and (2) Hennessy’s argument that the Section 155 claim was not within the scope of the arbitration agreement, and so was not arbitrable by its terms.

As to the first issue, Judge Posner rejected National Union’s preemption argument, and held that Section 155 is, indeed, a state law regulating the business of insurance:

Section 155 is a state regulation of the insurance business. Apart from the fact (not itself decisive) that it is part of the state’s insurance code, it is concerned only with the conduct of insurance companies

So (to paraphrase Cosell) down went the FAA. But not for the count. The Court then turned to the question of whether requiring Hennessy to arbitrate its claim under Section 155 would “invalidate, impair or supersede” the state statute, in violation of McCarran-Ferguson.

Hennessy said yes: citing intermediate appellate authority from Illinois, it argued that arbitrators are without authority to enforce Section 155, because that statute’s remedies are strictly limited to what a “court” may allow. But the ref court disagreed, on this ground:

When antagonists agree to arbitrate a dispute that could be made the subject of a court suit, an arbitrator or panel of arbitrators is substituted for a court.

Thus, while the clause in the CSA that prohibited the arbitrators from awarding “punitive damages, fines or penalties” might constitute a waiver of the parties’ right to pursue a claim under Section 155, it did not, by its terms, preclude the arbitration of such a claim.

On this basis, the court held that the FAA’s strong policy favoring arbitration did not invalidate or supersede Section 155. Rather, the FAA merely required that the Section 155 claim be resolved in arbitration—and that the cases holding that such claims were not arbitrable were simply wrong. Making his point with the usual flair, Judge Posner added that “Hennessy is not some hapless consumer who has to be protected by the courts from improvidently consenting to arbitrate a dispute with a big bad seller.”

The Court thus reversed the district court’s denial of National Union’s motion to compel arbitration, it ordered that the Section 155 claim be submitted to arbitration, and it further ordered that the lawsuit seeking payment under Section 155 be dismissed.

Image source: Florida Memory (Wikimedia)