A notorious moving target in the field of coverage litigation is an insurer’s responsibility under a commercial general liability policy for the policyholder’s faulty workmanship. The key question is usually whether the defect in workmanship is an “occurrence” within the meaning of a policy; the answer can depend on which court you ask or how those courts deal with other policy terms. In 2013, West Virginia’s highest court overruled its own precedents to hold that CGL policies cover faulty workmanship that causes personal injury or property damage. Last month, in BPI, Inc. v. Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co., No. 14-0799 (W. Va. May 20, 2015), the court further ruled that its decision applied retroactively—creating coverage in a policy that was sold while the overruled precedents still governed.

A notorious moving target in the field of coverage litigation is an insurer’s responsibility under a commercial general liability policy for the policyholder’s faulty workmanship. The key question is usually whether the defect in workmanship is an “occurrence” within the meaning of a policy; the answer can depend on which court you ask or how those courts deal with other policy terms. In 2013, West Virginia’s highest court overruled its own precedents to hold that CGL policies cover faulty workmanship that causes personal injury or property damage. Last month, in BPI, Inc. v. Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co., No. 14-0799 (W. Va. May 20, 2015), the court further ruled that its decision applied retroactively—creating coverage in a policy that was sold while the overruled precedents still governed.

The Looming Tower

In 2008, BPI was hired as a general contractor to construct a 300-foot cell phone tower, a cell tower compound and an access road, using plans engineered by another company. Within a year of the project’s completion, the access road collapsed. The cellular company filed a suit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky, alleging that BPI’s defective workmanship had caused the collapse. BPI promptly cross-claimed against Nationwide for a declaration that it was covered under its CGL policy.

When BPI and Nationwide filed cross-motions for summary judgment, the district court determined that the coverage issue was governed by West Virginia law, and that the law was unclear. For many years, damages from faulty workmanship were not considered to have been caused by an “occurrence” in West Virginia, because such damages “are a business risk to be borne by the contractor and not by his … insurer.” Erie Ins. Prop. & Cas. Co. v. Pioneer Home Improvement, Inc., 206 W.Va. 506 (1999). See also Corder v. William W. Smith Excavating Co., 210 W.Va. 110 (2001). But in 2013, the Supreme Court of Appeals decided Cherrington v. Erie Ins. Prop. & Cas. Co., 745 S.E.2d 508 (W. Va. 2013), which held:

Defective workmanship causing bodily injury or property damage is an ‘occurrence’ under a policy of commercial general liability insurance. To the extent our prior pronouncements . . . are inconsistent with this opinion, they are expressly overruled.

Since both the policy and the claim that were at issue in BPI pre-dated the Cherrington decision, the federal court certified the question of whether Cherrington applies retroactively.

Two Steps Backward

The Supreme Court began its analysis by noting that “appellate decisions are presumed to apply retroactively.” And while the opinion in Cherrington did not address the issue of retroactivity, the court noted that the 2013 decision concerned a policy issued in 2004. The issue, therefore, was whether “an exception to the general rule of retroactivity … [was] warranted.” To resolve that issue, the court considered six factors it had identified in Bradley v. Appalachian Power Co., 256 S.E.2d 879 (W. Va. 1979)—only some of which were relevant to the present case.

The first Bradley factor is “the nature of the substantive issue [that was] overruled.”

If the issue involves a traditionally settled area of law, such as contracts or property as distinguished from torts, and the new rule was not clearly foreshadowed, then retroactivity is less justified.

The fifth factor similarly asks “how radically the new decision departs from previous substantive law.” In the case of faulty workmanship, the court found that these factors did not argue against retroactivity, because “the definition of ‘occurrence,’ … was not an entirely settled area of law” before Cherrington. As an example, the court cited its Corder decision, which held that “[p]oor workmanship, standing alone, cannot constitute an ‘occurrence.'” In BPI, the court noted that Corder “did not explain the meaning of ‘standing alone’ … and did not address issues regarding … work performed by a subcontractor.”

The third Bradley factor considers whether a retroactive decision “has a relatively narrow impact and is likely to affect only a few parties.” With respect to Cherrington, the court found that retroactive application would affect only “a narrow portion of the law dealing specifically with insurance contracts where this type of provision becomes pivotal.” The court did not explain what criteria it used to make this determination about an issue that regularly arises before the courts of every state.

The sixth factor “look[s] to the precedent of other courts which have determined the retroactive/prospective question in the same area of the law.” The court found that “other jurisdictions” had come out in favor of retroactive application, although it cited only one example: Trinity Homes LLC v. Ohio Cas. Ins. Co., 864 F.Supp.2d 744 (S.D. Ind. 2012).

“For Someone to Win, Someone Else Has to Lose”

Finally, although it was not one of the factors named in Bradley, the court discussed the effect of retroactive application on “the insurer’s reliance interests.”

Although this Court recognizes that retroactive application of Cherrington presents a degree of unfairness to insurers who have presumably set their rates based upon a definition of ‘occurrence’ which differs from that announced in Cherrington, this ‘is a problem which is always encountered when there is a change in the law brought about by judicial decision.’

In support of its decision to tolerate “a degree of unfairness to insurers,” the court quoted a 1962 law review article by W. Page Keeton, the late Dean of the University of Texas School of Law, which criticized the view that “retrospective overruling in tort cases” is unfair to insurance companies:

[T]he implications of this view make it wholly unacceptable. … [I]ts general acceptance would … disable courts from creative decisions in accident law. … Ordinarily it is impossible to trace the impact of particular legal doctrines upon liability insurance rates. Also, even where the doctrinal change is one that might promptly affect rates, … there is a good prospect of the insurer’s spreading the loss among a group that comes fairly close to corresponding to the group of policyholders who might appropriately have been required to pay higher premiums if the overruling decision had been forecast.

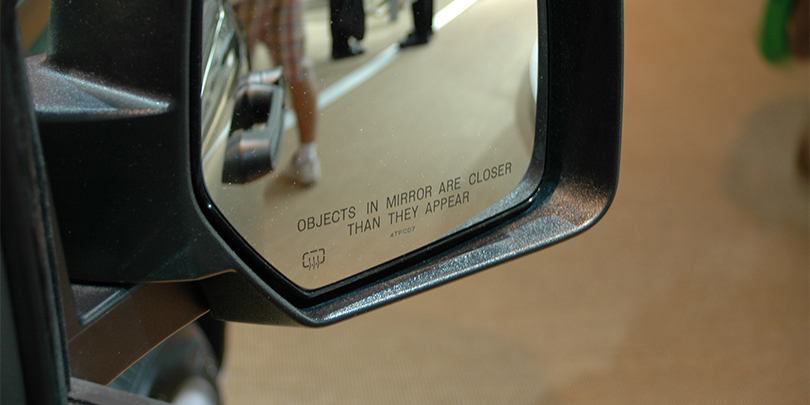

In other words, it’s up to insurers to look out for themselves. Nationwide might or might not have considered the possibility that courts would expand coverage for faulty workmanship when it priced BPI’s policy. But insurers are on notice that retroactive changes are now “a business risk to be borne by the contractor insurer.”

Image source: Axel Schwenke (Wikimedia)