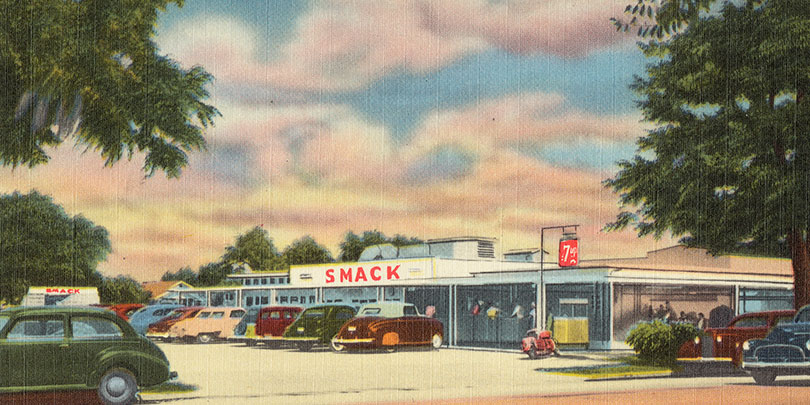

For many, Sonic Drive-In restaurants stir thoughts of juicy burgers, neon-blue sodas, ‘50s rock ‘n’ roll, and roller-skating carhops. Recently, however, in Hudson Specialty Insurance Company v. Brash Tygr, LLC, Nos. 13-1688, 13-1742 (8th Cir. Oct. 7, 2014), the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals served up an opinion in a commercial insurance coverage dispute with a little less flavor and fanfare, in analyzing the proper application of the “dual purpose” doctrine in the context of a non-owned auto liability endorsement.

For many, Sonic Drive-In restaurants stir thoughts of juicy burgers, neon-blue sodas, ‘50s rock ‘n’ roll, and roller-skating carhops. Recently, however, in Hudson Specialty Insurance Company v. Brash Tygr, LLC, Nos. 13-1688, 13-1742 (8th Cir. Oct. 7, 2014), the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals served up an opinion in a commercial insurance coverage dispute with a little less flavor and fanfare, in analyzing the proper application of the “dual purpose” doctrine in the context of a non-owned auto liability endorsement.

Tyler Roush was a managing member and 5% owner of Brash Tygr, LLC, the owner-franchisee of the Sonic Drive-In in Carrollton, Missouri, when he drove the car he owned jointly with his mother to deposit, at her request, her paycheck and to deliver personal mail to the post office. Though Roush had not worked at the Sonic in nearly twenty years, while at the bank he accepted from a bank employee bank deposit bags that the Sonic employees periodically used to make cash deposits. He intended to deliver them to his parents, who not only indirectly owned 70% of, but who also actively managed, the Sonic. Deposit bags in car, and driving toward the post office (in the opposite direction of the Sonic and in the same direction as his parents’ home), Roush struck and severely injured a pedestrian.

Brash Tygr was a named insured under a commercial general liability and commercial property insurance policy issued by Hudson Specialty Insurance Company. The policy included a Hired and Non-Owned Auto Liability endorsement that stated:

We will pay on behalf of the insured all sums that the insured shall become legally obligated to pay as damages because of “bodily injury” or “property damage” arising out of the use of a “non-owned auto” by any person other than you in the course of your business.

The dispositive question for the Eighth Circuit Court ultimately became whether Roush’s car was being used “in the course of [Brash Tygr’s] business.”

Lower Courts

In a personal injury action filed by the pedestrian in Missouri state court, the Brash Tygr, Roush, and his parents – each of whom were individually named as defendants — declined Hudson’s offer of a defense under a reservation of rights. They thereafter admitted, in response to plaintiff’s requests to admit, that Roush had been operating the vehicle for a business purpose. They entered into a settlement agreement that amounted to a stipulated judgment, which judgment was thereafter entered by the Court, which made findings of fact based on the admissions, reciting that the action “was tried to this Court with all parties represented by counsel” and awarding plaintiffs $5.3 million in compensatory damages against all defendants and $500,000 in punitive damages against Tyler Roush and Brash Tygr.

Meanwhile, Hudson brought a declaratory judgment action in federal district court seeking a ruling that there was no coverage because the vehicle was not being used in the course of the insured’s business. On cross-motions for summary judgment, the district court rejected the insureds’ argument that Hudson was collaterally estopped from asserting its coverage position based on the state court judgment, because Hudson had no opportunity to litigate the coverage issue in and was not a party to the state court action. Nevertheless, it found the state court’s findings of fact were undisputed, and thus granted the insured’s motion for summary judgment (and denied Hudson’s), holding that Roush was using his car “in the course of [Brash Tygr’s] business.”

The “Dual Purpose” Doctrine

Hudson appealed, and the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals took a closer look at the “dual purpose” doctrine. It cited the Missouri Supreme Court’s holding that, for a personal errand to have a dual purpose such that it is also “in the course of [an employer’s] business”:

It is enough that some one would have had to make the trip to carry out the business mission. If the trip would ultimately have had to be made, and if the employer got this necessary item of travel accomplished by combining it with the employee’s personal trip, it would be a concurrent cause of the trip, rather than an incidental appendage or afterthought. There is no occasion to weigh the business and personal motive to determine which is dominant.

Corp v. Joplin Cement Co., 337 S.W.2d 252, 255 (Mo. 1960) (en banc) (citing then-Judge Cardozo’s analysis of the doctrine in Marks’ Dependents v. Gray, 167 N.E. 181, 183 (N.Y. 1929, additional emphasis supplied)),

The Eighth Circuit Court held that, while the underlying state court correctly stated the dual purpose doctrine, it nevertheless misapplied it. The Eighth Circuit Court noted that, while the state court had found that Roush acted with the “concurrent purpose” of serving both personal and business interests, it made no finding that, absent Roush accepting the bank deposit bags, “some [employee or agent of Brash Tygr] would have had to make the trip to carry out the business mission.” Roush had never picked up bank deposit bags, nor did Sonic employees ever make special trips to the bank to retrieve deposit bags. Rather, the deposit bags were unnecessary for the Sonic’s banking needs. As the Eighth Circuit Court put it, “picking up the bags was a matter of convenience, not necessity, for Brash Tygr and the Sonic Drive-In.” Notably, one of the panel judges dissented on this dispositive point, questioning the majority’s holding that the state court’s findings of fact, which the dissenter argued were all undisputed in the coverage action, failed to sustain the insureds’ burden of proof on the question of “dual purpose” as a matter of law.

Collateral Estoppel

The Eighth Circuit Court also addressed the district court’s ruling rejecting the insureds’ collateral estoppel argument. It affirmed on this point, holding that, because the insureds rejected Hudson’s tender of defense in the state court action, Hudson was not in privity with any party in the underlying action, and did not have “any opportunity, let alone a full and fair opportunity, to litigate coverage issues” in the state court action.

The Eighth Circuit Court thus reversed the district court’s grant of summary judgment in favor of the insureds, affirmed the district court’s ruling on estoppel, and remanded to the district court with directions to enter judgment in favor of Hudson on the coverage issue.

Image source: Boston Public Library (Flickr)