In an effort to clarify over 20 years of conflicting precedent, the Texas Supreme Court announced five rules that, according to the court, explain the relationship between claims for breach of insurance policy and extra-contractual claims for bad faith and violations of the Texas Insurance Code. USAA Texas Lloyds Co. v. Menchaca, No. 14-0721, slip op. at 6 (Tex. April 7, 2017). Although an insurance policy is an agreement between the parties that is generally governed by the principles of contract law, due to the nature of the relationship, insurers owe certain extra-contractual common law and statutory duties of good faith and fair dealing. In Texas, such extra-contractual duties are codified under Chapters 541 and 542 of the Texas Insurance Code.

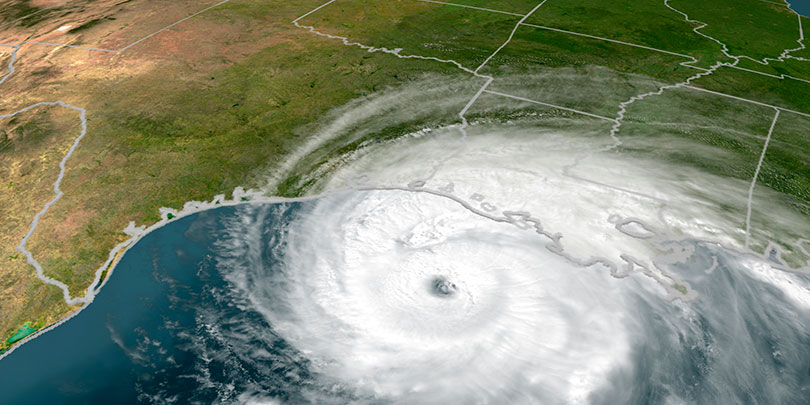

In Menchaca, the insured, Gail Menchaca, filed a first party claim with her insurer, USAA Texas Lloyds Company (USAA), under a homeowner’s policy for damages that her home allegedly sustained as a result of Hurricane Ike. The adjuster who investigated Menchaca’s home found only minimal damage and although USAA determined there were some covered damages, it denied the claim because the damages were below the amount of the policy deductible. When Menchaca complained, USAA sent another adjuster to re-inspect the home, but again denied coverage. Thereafter, Menchaca brought suit against USAA alleging breach of insurance policy and unfair settlement practices in violation of the Texas Insurance Code.

After trial, the jury found that USAA did not breach the insurance policy. Nevertheless, the jury found that USAA did violate the Insurance Code by failing to conduct a reasonable investigation before denying the claim, and awarded damages in the amount that would have been owed if the claim had been covered under the policy. Despite the jury’s finding on breach of contract, the trial court entered judgment in favor of Menchaca and the court of appeals affirmed.

The primary issue before the Texas Supreme Court was whether, despite a finding that an insurer did not breach the insurance policy, an insured can nonetheless recover policy benefits on the basis that the insurer violated the Texas Insurance Code. The court, however, recognized that precedent in this area was unclear and that substantial confusion existed among courts and industry members and their counsel. Consequently, the court took the opportunity to address in detail the broader issues surrounding when a policyholder may and may not recover extra-contractual claims against an insurance company — at least in first party claims. The court analyzed the conflicting precedent and promulgated five new rules governing the relationship between contractual and extra-contractual claims:

- General Rule. An insured cannot recover policy benefits for an insurer’s statutory violation if the policy does not provide a right to receive those benefits.

- The Entitled-To-Benefits Rule. An insured can recover policy benefits as actual damages under the Insurance Code even if the insured has no contractual right to those benefits, if the statutory violation causes the loss of the benefits or the insurer’s conduct caused the insured to lose that right.

- The Benefits-Lost Rule. Even if the insured does not have a right to recover policy benefits under the contract, an insured can recover such benefits if the insurer’s conduct caused the insured to lose that right.

- The Independent-Injury Rule. The court set out two aspects of the rule:

- if the insurer’s statutory violation causes an injury independent to the insured’s right to recover policy benefits, then the insured may recover for that injury even if the insured does not have a right to recover for such under the policy; and

- an insured cannot recover any damages beyond the policy benefits unless the insurer’s statutory violation causes an injury that is independent from the loss of benefits.

- The No-Recovery Rule. An insured may not recover damages for a carrier’s Insurance Code violation if the insured had no right to receive benefits and sustained no independent injury.

Because USAA did not breach the insurance policy, Menchaca was effectively not entitled to coverage under the policy unless the violation caused her damages. Thus, the court held that the trial court and the court of appeals erred in disregarding the jury’s finding on breach of contract. However, given the conflicting precedent and confusion that existed at the time the parties argued the case, the court remanded it to be retried pursuant to the new rules it promulgated.

To prevail in the new trial, Menchaca will have to argue that, inter alia, USAA’s alleged statutory violation caused her damages. Similarly, going forward, insureds seeking to recover extra-contractual damages against insurers will likely have to argue causation.

Moreover, while the Menchaca case generally clarifies that where there is no coverage, there can be no damages, it also stands for the narrow proposition that not all bad faith claims will be barred in circumstances where there is no breach of insurance policy. Such circumstances remain undefined, however, and it will likely take further litigation between insureds and their insurers before Texas courts provide more clarification.