Approximately twenty percent of Americans have been classified as chronic procrastinators, which means one in five policyholders faces a potential problem when suing for coverage. While the statute of limitations for breach of contract varies by state, it is typically three years or more. However, insurance policies often impose their own, contractual suit limitations, and it is often only a year or two. When and how these provisions operate to bar coverage varies under the circumstances. Some recent decisions highlight the fact that, unlike notice provisions, they are often applied rigorously, without regard to whether the insurer was prejudiced, and whether or not enforcement results in a disproportionate forfeiture to the insured.

In Dilley v. Auto-Owners Ins. Grp, No. 14-1240 (Iowa Ct. App. Dec. 23, 2015), Iowa’s Appellate Court recently affirmed a summary judgment ruling against a policyholder who waited until the last day before the end of a two-year contractual suit limitation period to sue her auto insurance company for underinsured motorist benefits. Unfortunately for her, the plaintiff named the wrong entity in the lawsuit, bringing her suit against “Auto-Owners Insurance Group” (a non-existent entity), rather than Owners Insurance Company, whose name appeared on her policy. She sought to add the correct party after the suit limitation period had ended, and she argued that the claims against the newly-added entity should relate back to the date of her complaint—in which case they would not be barred by the suit limitation period. The trial court disagreed, and the Appellate Court affirmed, finding that the plain terms of the insurance policy controlled.

In B.S.C. Holding, Inc. v. Lexington Insurance Company, No. 14-3131 (10th Cir. Sept. 15, 2015), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit examined the issue of whether an insurer must demonstrate prejudice before it can enforce a suit limitation provision. The case involved a salt mine that first experienced problems in 2004, when its operators discovered that the space between the floor and ceiling was contracting at an abnormally high rate. In September 2005, a consultant advised that water might be entering the mine, creating a “huge problem” of abnormal closure rates. By the end of 2006, one portion of the mine had closed by over ten feet. In early 2008, a water leak was discovered, and, two years later, a panel of experts concluded 2010 that an improperly-sealed well had resulted in deformation in the rock above the mine, causing many of these issues. In May 2010, the insured sued for coverage.

The insurance policy at issue required that all suits must be commenced within twelve months of the discovery of the underlying loss. The policyholder noted, however, that Kansas applies a “notice prejudice” rule, under which an insured may be excused for late notice of a claim, if the insurer was not prejudiced by the late notice. The insureds argued that the same rule should extend to application of a policy’s suit limitation provision. The Tenth Circuit rejected the argument; it held that the suit limitation provision was unambiguous, and barred the claim.

Similarly, in Hawley v. Preferred Mutual Insurance Company, No. 14-P-917 (Mass. App. Ct. Sept. 16, 2015), a landlord received notice in June 2004 of a water leak that eventually caused a ceiling to collapse. The landlord gave prompt notice to the insurer, who determined that the water leak was the result of a crack in a bathtub, which became exacerbated through continued use. The insurer provided notice in November 2004 that it was denying the claim. Some nineteen months later, the insured sent the insurer notice of violations, and it requested arbitration a mere five days before the statute of limitations ran. The insurer declined arbitration. The insured filed suit in June 2008.

The policy incorporated the statutory, two-year statute of limitations for insurance coverage claims, which also provides that an action must be commenced within two years of the loss, absent a referral to arbitration. If arbitration commences, the statute is tolled until 90 days after any arbitration award.

In this case, the arbitration never began, because the insurer declined it. Thus, in granting summary judgment to the insurer, the trial court held that there was no tolling of the statute, and so that the claim was barred by the suit limitation period.

On appeal, the Massachusetts Appellate Court agreed, noting that, where the insured waits until the eve of a statute of limitations to make a request for arbitration, “it was open to [the insured] to file their complaint timely, while requesting . . . that the court delay commencement of the action,” until the insured has accepted or declined arbitration. Because Massachusetts has specific mechanisms in place allowing an action to be filed and then stayed to toll a statute of limitations, the court felt that insureds running up against the deadline do not need any additional protection.

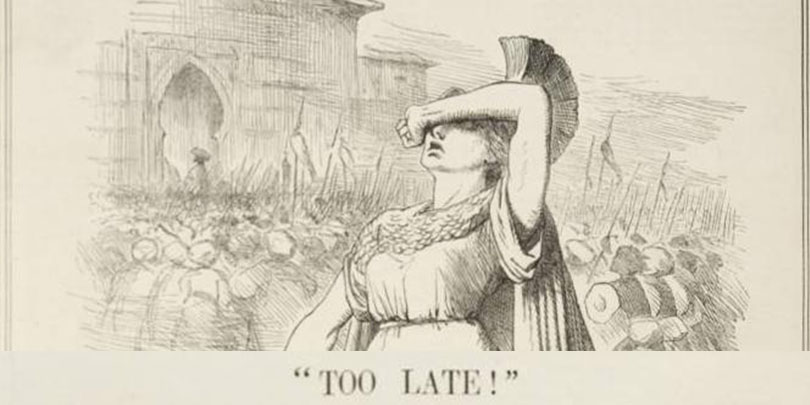

Thus, unlike late notice defenses, which are often subject to prejudice analyses that sometimes bar application of the defense, suit limitation periods are strictly construed according to their plain terms. While the early bird gets the worm, and the second mouse gets the cheese, an insured who procrastinates in suing for coverage may very well wind up with nothing.

Image source: Punch (Wikimedia)